On Culture and Barbarism

The theft of a Master's Thesis – a new peak in national plagiarism thought. Students often plagiarize the works of their professors, but could plagiarism work in the opposite direction, with a professor stealing from a student? It turns out that for our plagiarists, nothing is impossible. Let me introduce you to the latest domestic "innovation." The professors and thieves are Ivan Vasylovych Danyliuk, Dean of the Faculty of Psychology at Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv and Doctor of Psychological Sciences, along with two of his subordinates: Inna Valeriivna Kozytska, Head of the Department of Experimental Psychology, and Serhii Oleksandrovych Shykovets, a postgraduate student:

In October 2017, I defended my master's thesis, titled “The Structure of the Cultural Syndrome ‘Individualism-Collectivism’ in Ukraine,” at the same university. The chair of the examination committee was Ivan Danyliuk, a well-known Ukrainian ethnopsychologist. Unfortunately, during the defense, he showed no interest in my work. He was either talking on the phone or complimenting the female committee members. Not once did he turn his head to look at the presentation, even though it would have required just a slight tilt. To be fair, he did flip through my thesis. However, he asked no questions, which surprised me, as I don't think defenses in his field of expertise occur very often. In the end, the committee awarded me 92 points (excellent).

And so, recently, while preparing an article for publication based on the results of my thesis research, I was browsing the latest literature online—had anyone done anything in this area over the past four years? I came across an article by Danylyuk, Kozytska, and Shykovets. What an intriguing title! Could they have replicated my research? But… what’s this? Something painfully familiar, though written in terrible English... Why, it’s my thesis, word for word! I won’t describe my emotional state upon seeing this. That’s something I’ll detail in court when the time comes. For now, let’s stick to the bare facts.

For convenience, let’s compile comparative tables.

In the left column is the article: Danyliuk I. V., Kozytska I. V., Shykovets S. O. The cultural syndrome "individualism-collectivism" and its psychological peculiarities including well-being of regional communities' representatives in Ukraine. // Fundamental and Applied Researches in Practice of Leading Scientific Schools. – 2018. – 30, 6. – P. 55–61 (it can be viewed in a new window here; downloaded here; viewed on the journal's web-archived site here).

In the right column is: Borysenko L. H. The structure of the cultural syndrome “individualism-collectivism” in Ukraine / Master’s Thesis, Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv, Kyiv, 2017. – 105 p. (Ukrainian original - can be viewed here, downloaded here, on Researchgate here; English translation - view here, download here, on Researchgate here) (Note: Page numbers reflect the Ukrainian original; pagination may differ slightly in the English translation)

First, let’s compare the numerical data.

Now let's compare the texts.

Thus, all 163 numerical values from the article match those from the thesis, including all decimal points, italicization, and bold formatting. Even one incorrect value is identical—the Kendall correlation coefficient of 0.53, which I mistakenly recorded from the SPSS program instead of the correct Spearman correlation of 0.75.

The only number that doesn’t match is the 120 respondents claimed by Danyliuk et al. instead of 604 in my thesis. However, as shown earlier, they report 495 degrees of freedom, which corresponds to a sample size of 500 participants—the exact number I used for the factor analysis!

As for the article's text, 76% of it matches the text of my thesis. The remaining 24%—which doesn’t match—includes part of the abstract (repeated verbatim in the conclusion) and the introduction. Their attempts to “improve” the thesis text consisted of inserting citations—entirely at random.

Let’s examine how Danyliuk et al. “improved” a section containing definitions of culture. In my thesis, I don’t include the citations listed in their article because I quote all authors from the monograph by Kroeber & Kluckhohn (1952), as I explicitly state. I selected definitions of culture from Tylor, Benedict, Boas, Malinowski, and others, purely based on personal preference—they resonated with me in some way. I included them in my thesis in my own Ukrainian translations.

What do Danyliuk et al. do? They take my Ukrainian translation, run it through Google Translate into English, and for credibility, add citations as if they referenced the original sources! This is nothing short of mockery of the classics of cultural studies.

Here’s the masterpiece they created:

What does this accumulation of amateurish nonsense indicate? It shows that neither the original sources, nor the comprehensive monograph by Kroeber and Kluckhohn, nor even Hofstede's book—one of the most cited scientific works of the 20th century—have ever been seen by Danyliuk et al. The citations were placed at random, purely for aesthetics or as a means to promote their own article, Danyliuk & Shykovets, 2018.

The title of the article and parts of the text also feature phrases like “psychological well-being of personality” and “well-being of regional communities' representatives in Ukraine.” They attempt to explain this psychological well-being through the results of my study. However, the connection between psychological well-being and cultural syndromes remains shrouded in mystery. This is yet another "improvement"—an effort to add something seemingly intellectual and scientific to the text.

Can all these similarities be explained without acknowledging plagiarism? According to Danyliuk himself and some of his colleagues, all similarities are the result of a remarkable coincidence of scientific ideas.

Here is a letter from a well-known Ukrainian psychologist:

Ukrainian original (opens in a new window)

It’s clear that the reference to penicillin stems from ignorance of the history of its discovery, but why appeal to emotions and war? Why resort to threats?

No, the plagiarism committed by Danyliuk, Kozytska, and Shykovets is entirely real. Moreover, it is deliberate and fully conscious. They knew exactly what they were doing. The statement in the article, “Source: data from the original author’s research, 2018”, is an outright lie. No such research by them in 2018 ever existed. And they are well aware of this, intentionally deceiving the academic community.

Danyliuk and his co-authors claim that they conducted research involving 120 respondents, 30 from each of Ukraine’s regions (Central, Western, Eastern, and Southern). They even provide details about the respondents’ ages—between 17 and 33—and state that the gender distribution neatly aligns with 40% men and 60% women. This is blatant fabrication designed to lend credibility to their work. However, even in this small original fragment, they managed to make errors—as I mentioned earlier, their lack of understanding of basic statistics betrayed them.

During my defense, Danyliuk served as the chair of the examination committee. However, long before the defense, he was aware of my research. Back in 2015, I had approached him to ask if he could supervise my term paper, but he declined, citing a heavy workload. Shykovets has been, and still is, subscribed to my publications on Academia.edu. I discussed my research with Kozytska during a seminar on experimental psychology, which she taught.

In 2017, I attempted to read the thesis of Terezia Viktorivna Yatsenyuk, the wife of the then-Prime Minister, who studied in the same group as me. Let me just say: I had certain doubts that her thesis met the required standards and deserved a high grade. The university’s response was as follows:

Ukrainian original (opens in a new window)

From all this, it follows that not just anyone can touch the sacred grail of Ukrainian educational thought—a thesis. I have no doubt that it was Danyliuk who obtained the electronic copy of my thesis from the Institute of Continuing Education and that the idea for the publication belonged to him. He likely assigned the task of reworking the text so it wouldn't be recognizable to his student, Shykovets, who managed it rather poorly. Kozytska was probably added to the project later. The fact that the source of the article was the electronic copy of my thesis, which I sent to the Institute of Continuing Education for a plagiarism check before the defense (a mandatory procedure), is confirmed by identical typographical errors and text highlights.

Danyliuk and company not only stole my research but also thoroughly disfigured it. Here are just a few examples of their clumsy and unprofessional writing:

- “Space measurements of individualism-collectivism” – such a concept does not exist. I came up with the term “spatial measurement” myself when I was considering how to present two different approaches I used to measure individualism-collectivism within a single work. That’s why I put this term in quotation marks. Research involving time series can obviously be called a temporal dimension. By analogy, the measurement obtained from a questionnaire given to respondents, I called a “spatial dimension” because it’s like a momentary snapshot of a parameter here and now. However, this is a very conditional term, invented solely to combine two approaches under a single heading. I would never have phrased it that way in an academic article. The questionnaire approach, of course, can also be used to study temporal changes. As we can see, Danyliuk et al. didn’t even grasp what it was about. In Table 1, they call it “space measurement,” while in the text (p. 56), they already refer to it as “dimensional structure.”

- Ethnometry (етнометрія), a term used mainly in post-Soviet literature. This concept is not employed in English-language cultural studies.

- When researching differences between Ukrainian-speaking and Russian-speaking regions, what matters is not where the respondent currently lives but the region where they spent the majority of their life. That’s why I included both indicators (RegionA and RegionB in the table on p. 58). However, the plagiarists in their two identical Tables 2 and 4 only provide the first factor – where the respondent currently lives. For any serious reviewer, this is a red flag.

- Other groups of pronouns from my Table 3.6, such as third-person plural pronouns, did not interest Danyliuk et al. What’s the point of presenting research results on pronouns if not all pronouns are analyzed? They copied the conclusions of the thesis verbatim, even though my thesis included not only a broader study of pronouns but also a measurement of values using Schwartz's methodology, which they don’t even mention in their article.

- Not a single word in the article explains how the English-language questionnaire by Singelis et al. (1995) was used. However, this is clearly detailed in my thesis: I personally purchased the rights to use this questionnaire from the publisher (yes, it is copyrighted), translated it into Ukrainian, and conducted statistical studies to determine whether it worked as intended.

- The statistical stuff – degrees of freedom, multiple regression, correlation. Are the Dean of the Faculty of Psychology and the Head of the Department of Experimental Psychology truly familiar with the basics of psychological statistics? I have already written about the degree of freedom of 495 for 120 respondents. In Table 3, Danyliuk et al. “aligned the rows,” resulting in a situation where regression coefficients for age and gender are entirely absent. This suggests that they have no understanding of what multiple regression is, how its results should be presented, which variables are dependent, which are independent, what influences what, what regression coefficients are, and what they signify. Now let’s move to their Table 6. From my large table on p. 69, they only took the Spearman correlation values but labeled them as “statistical characteristics” without providing any further explanation. Do they even realize that they are reporting correlation coefficients between certain variables? Do they have any understanding of what correlation actually is?

I also filed complaints with the university and the Ministry of Education and Science. The responses I received were as follows:

Ukrainian original (opens in a new window): 1 2 3

As evident, the university diligently avoids using any negative terminology in reference to Danyliuk and his co-authors. Not a single word is mentioned about whether plagiarism occurred. Any acknowledgment of violations can only be inferred "between the lines," and even then, with great effort. In the response from First Vice-Rector Volodymyr Ilchenko, it is merely stated that the violation of my copyright has already been "resolved" because Danyliuk "retracted" the article. Allegedly, this is evidenced by "the absence of pages 55–61, where the article was located, from the journal's content." However, these claims are false or even deliberately misleading.

According to the instructions on the journal's website, before publication, authors transfer their rights to the article to the publishers and the journal's editorial board by completing a special form, granting rights "to publish the article and distribute its electronic copies across all electronic media and formats (posting on the journal's website, any electronic publication services, electronic databases, or repositories)" (quote from the copyright transfer agreement on the journal's website https://web.archive.org/web/20220703052310/https://farplss.org/index.php/journal/transfer-of-copyrights). Moreover, a single author cannot act on behalf of all authors. The authors of a publication, acting together, can only initiate the retraction process, but this requires substantial grounds, such as falsified data or copyright violations. One author cannot "retract" a scientific publication after it has been officially published simply because they wish to do so.

Obviously, the retraction process can be initiated not only by the authors but by anyone. Upon receiving such a request, the journal is required to conduct an investigation. If a violation is confirmed, the journal officially retracts the article. Retraction of scientific publications involves issuing a notice on the journal's website and/or in the printed issue about the retraction and its reasons. The article may remain on the journal's website marked as retracted. This allows everyone to access and evaluate the reasons, which can vary—from unintentional errors to malicious plagiarism. For this reason, a retracted article might even be cited more frequently than one that is not, though the nature of such citations will, of course, differ. This retraction procedure is outlined by COPE (Committee on Publication Ethics). Once retracted, the article officially loses its status as a scientific publication, and all its results are considered unpublished.

An analysis of the journal's website confirms that the article was indeed removed around June 2022 from the journal's content: it is available in the content of the journal's web-archived site on January 23, 2022 (link); available as a downloadable paper on May 20, 2022 (link); but not available in the content on July 03, 2022 (link) where pages 55–61 are absent. However, there is no notice on the journal's website explaining the reasons for this, and the article itself is also missing from the site. This resembles a covert cover-up of the violation rather than an official retraction. The article continues to be indexed in scientific databases, and numerous copies are available online on various academic resources, meaning the article still exists as an official scientific publication. The lack of a notice on the journal's webpage leaves open the possibility that the article could reappear there.

Moreover, Danyliuk and his co-authors continue to share the text of the article on their pages on social networks for academics and specialized academic sites, and they list the article in their scientific publication records!

The university's response also uses the term "removal from publication." So was the article "removed from publication" or "retracted" after being published? These are different things.

All of this continues to prevent me from publishing my own results, as reputable journals are unlikely to accept them. They will assume that I am the plagiarist, and no explanation from the university will make a difference. What truly matters is whether the journal officially retracted the article, and if so, where is the journal's formal statement confirming this?

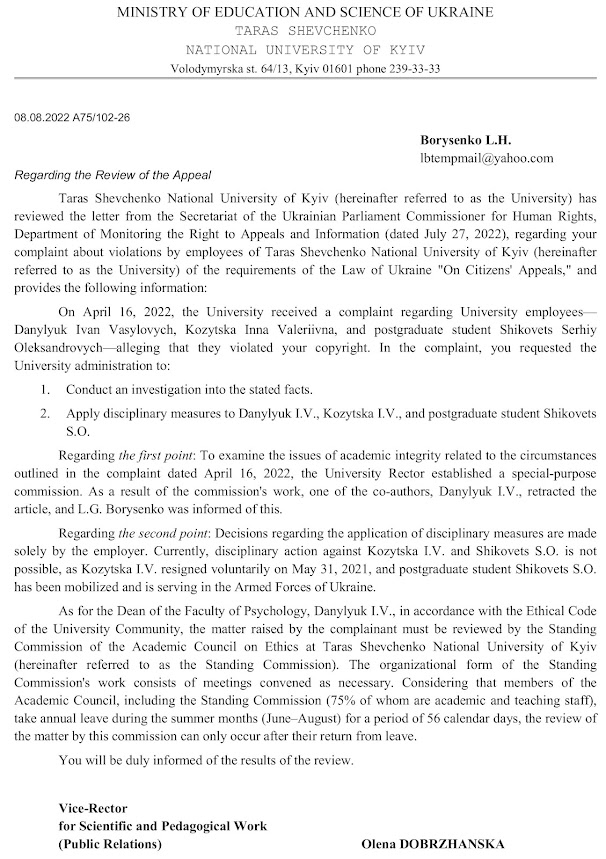

Dissatisfied with this response, I filed a complaint with the Ombudsman. After the Ombudsman's intervention with the university, progress started to be made:

Ukrainian original (opens in a new window)

And finally, after filing a lawsuit in the administrative court and two weeks after the proceedings were initiated, the university finally decided to provide the commission’s conclusion, where the fact of plagiarism committed by Danyliuk et al. was unequivocally stated:

Ukrainian original (opens in a new window): 1 2 3 4

As a result, the correspondence with the university, the Ombudsman, and filing a lawsuit took six months.

However, the university was not merely stalling for time. Amid this exchange of letters, some intriguing events unfolded. On August 11, 2022, without waiting for the completion of the legally prescribed five-year period that began in October 2017, the university decided to... destroy my thesis.

Ukrainian original (opens in a new window)

Here is what I received from the university in response to my inquiry about the retention period for thesis papers:

Ukrainian original (opens in a new window)

All of this leads to some unpleasant thoughts. Why the rush?

I have not received any letters or apologies from Danyliuk and Co. They continue to insist that this entire story is just a coincidence. There are only two possible options here – either these people are pathological liars, or they are simply professionally incompetent. In the case of pathological lying, if the person also claims to be a psychologist, then both options come under one roof.

It seems like this is such a case.